State and Genocide in Italian Libya

Quick Summary

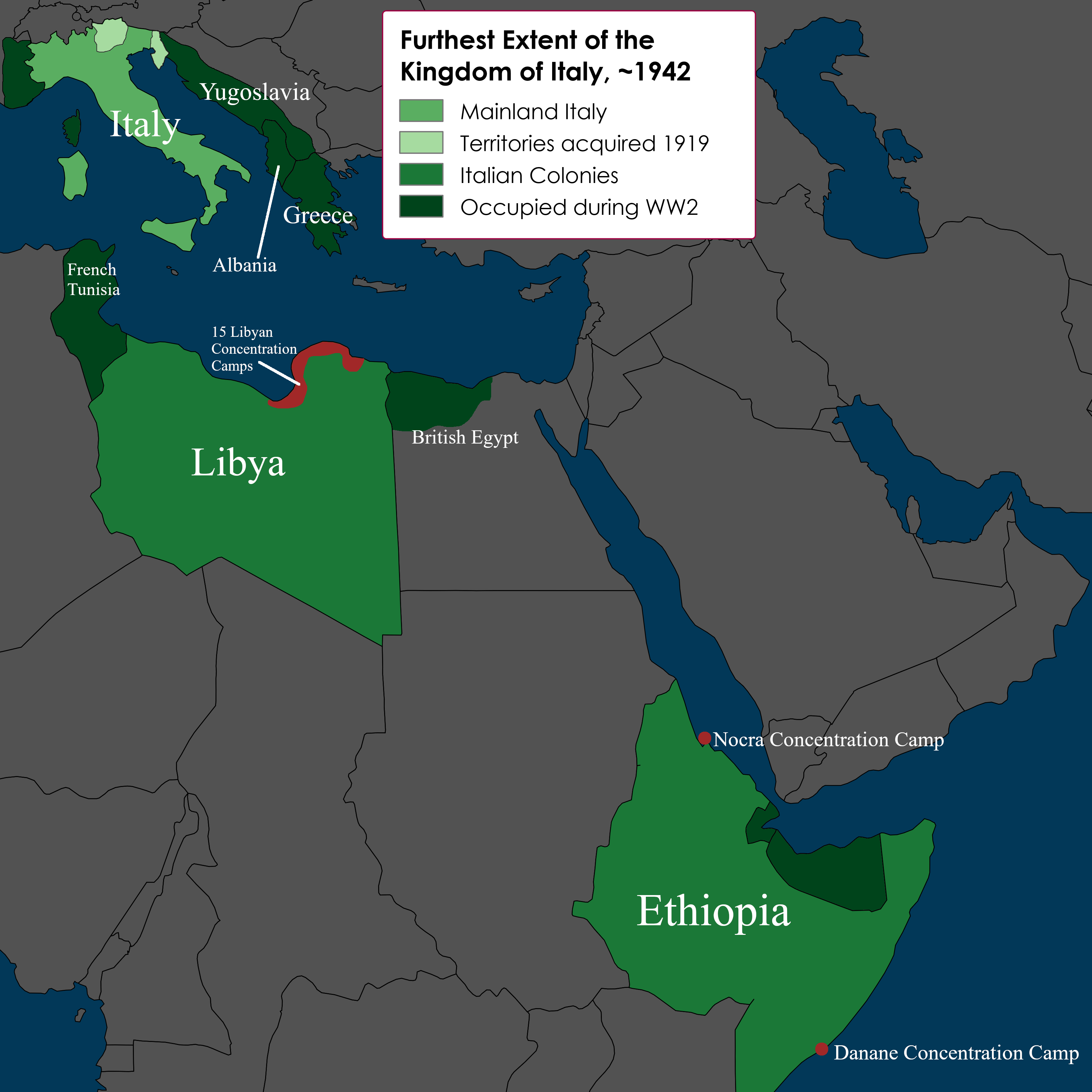

This is the full text of my undergraduate thesis paper I wrote from January to May 2024. It tells the tale of the genocide committed by the Italian Fascist government in their colony in Libya from 1911 to 1945. Because this is an academic text rather than a more public-oriented piece of history, it is a much more dense piece of writing compared to the Origins of Fascism article. I base my analysis of the genocide in the contrast between what I call the "prerogative" and "normative" impulses of state. This is an old analytical tool for studying Fascism which I evolved upon to try to show what motivated the Italians to pursue such a brutal policy in Libya. If you'd like to read it, the paper is 6,500 words long. I have reformatted the paper and added some images while adapting it to the website, but it is otherwise unchanged.

Introduction

In 1938 Mussolini sponsored the publication of the Manifesto of Racial Scientists. The Manifesto stated that the Italian people constituted a race which was biologically distinct from Africans and other Europeans. It also proposed that the Italian race needed to be preserved through discrimination against Jews and Africans. The Manifesto was followed by a series of discriminatory laws known as the 1938 Race Laws. The laws, applying both to Africans and Jews in Italy, banned racial groups from membership in the Fascist Party, employment in government, interracial marriage, access to public school at all levels of education, and other measures. The effect of the laws, overall, was to remove Jews and Africans from public life in Italy entirely. The Manifesto and the Race Laws came as a surprise to many Italians and the rest of the world. Fascism had lacked any explicit legal discrimination against Jews from 1922 to 1938, and some Jews had even been members of the Fascist party in its early days. The discriminatory character of fascism had been easy for many to ignore so long as it only existed in its African colonies. Historians have largely glossed over the connection between the Race Laws and the colonies in Africa, mainly focusing instead on their antisemitism and connection to the Holocaust. However, the 1938 Race Laws are inextricably linked to the Fascist system of governance and the colonizing goals held by that regime.

Italian colonial interests in Libya date back to the 1890s, when the nations’ then Liberal government began expanding its commercial and cultural influence in the region . Libya was targeted for a series of political and economic reasons which became a violent desire for land in the early 1900s. An economic crisis in 1907 evolved, in Italy, into a political scandal involving the Bank of Rome in 1910 which saw Italian political culture drift towards more overt right-wing nationalistic sentiment. One of these sentiments involved the belief that Italy was a “proletarian nation”, a weak nation surrounded by stronger imperialistic forces. The proletarian nation concept was used to justify colonialism – the only way for Italy to become strong was to follow the colonizing examples of strong nations. Along the north-African coast most land had already been seized by opposing colonial powers – Morocco to Tunisia was occupied by the French, while Egypt was controlled by the British. Libya, however, was held by the weak and vulnerable Ottoman Empire. In 1911 Italy attacked multiple Ottoman strongholds in Libya, and the Ottomans, unwilling to risk open war with Italy or embarrass themselves by surrendering, granted independence to the Sanusi Order. By 1913 the Italian military had occupied Libya but did not entirely control it.

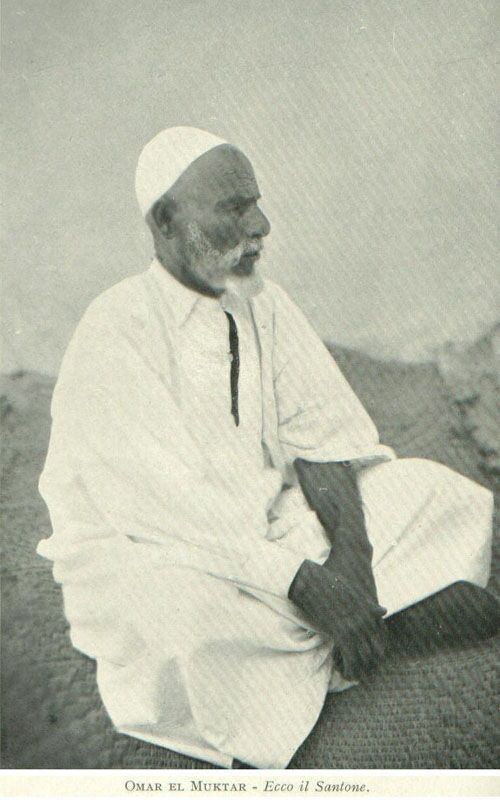

During the 19th century Libya had been controlled by two forces: the Ottoman administration and the political-religious institution called the Senusi Order. The Senusi Order began as a political movement named after its founder Muhammad b. Ali al-Sanusi (1787-1859). Its roots were in al-Sanusi’s Islamic faith coupled with a deep distrust of colonizing European powers. During the 1800s the movement grew into a dominant political force within the Libyan interior, while the Ottoman administration remained strongest on the coastline. The Senusi Order evolved into a semi-governmental organization, integrated into the various tribal families that inhabited the Libyan interior. Senusi mosques became centers of education, trade, and non-state power; Senusi administrators collected taxes from the leaders of tribal families in villages. When the Italian Fascists arrived, the Senusi evolved into a highly effective resistance force led by ‘Umar al-Mukhtar.

The Senusi fought a highly effective guerilla war against the Italian military. The source of Senusi power was in its ability to recruit from local tribesmen, who after fighting could return home back to their villages and resume civilian life. The Senusi were therefore able to “move” extremely effectively, recruiting briefly from local villages to conduct military action before retreating back into larger Libyan society and their power base in the interior. Unable extend military control beyond the Libyan coastline, Italy granted autonomous control of Libya to the Senusi Order during World War One.

After the war, in 1922, Mussolini staged his March on Rome, which saw the Fascist party take over the Italian government. The Fascists, much like the Liberals during the original invasion in 1911, viewed Libya as a strategic “gateway to the East” from which they could further influence affairs in Africa. The Fascists hoped that by controlling one Muslim region in Africa, they could influence the rest of the Muslim world. The Fascists additionally hoped to create a new economic and agricultural base in the region. In 1923 the Fascists abandoned the conciliatory attitude taken by the previous administrations, “declaring that Libya was essential for settling Italian peasants and thus eliminating any compromise; only force would succeed in clearing the land for settlement.” However, the Italian military campaign proved to be incapable of destroying the Sanusi Order, which continued its guerilla war under the leadership of ‘Umar al-Mukhtar for 6 years.

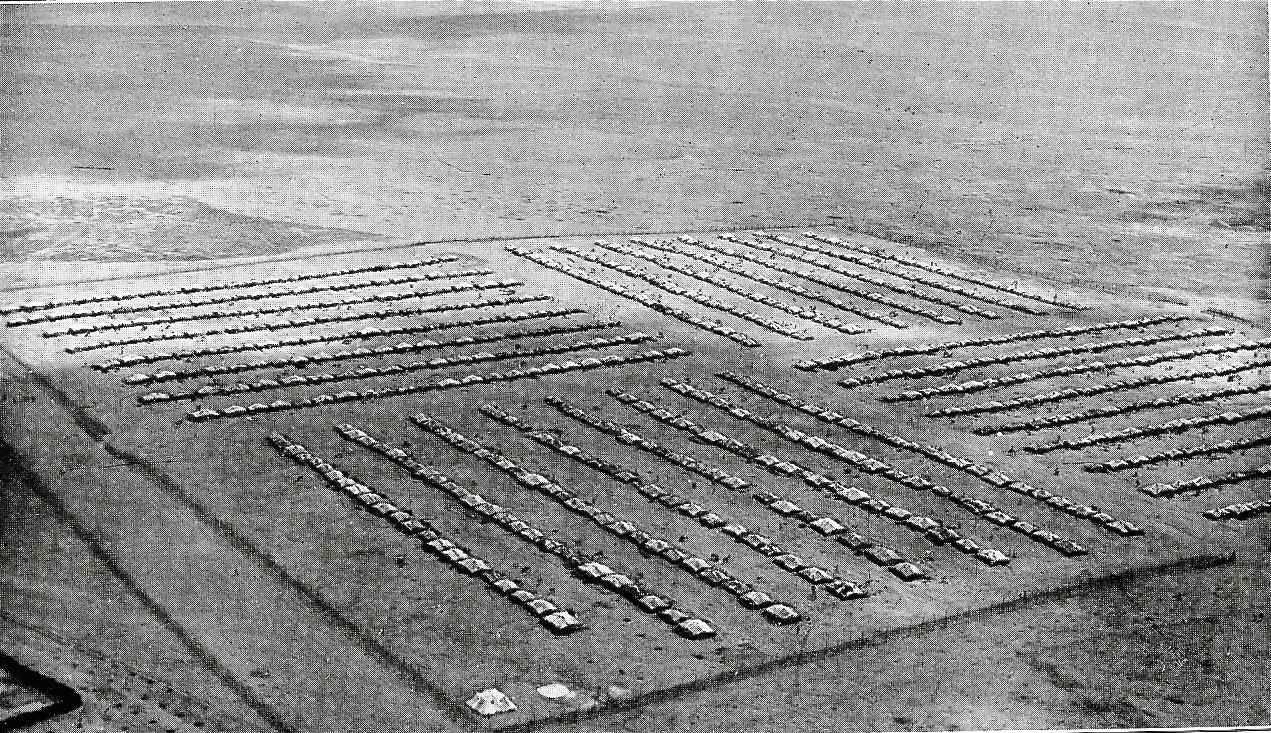

In 1929 the Italians employed a new strategy which targeted not the Senusi order but instead the Libyan people. Because the Senusi derived their power from their connections with the Libyan tribespeople, the Italian military hoped to sever the tribes from the Senusi leadership. Concentration camps were constructed in the north-eastern region of Libya, which had been deemed the province of “Cyrenaica” by the Fascist administration. In the concentration camps the tribespeople were heavily surveilled and banned from leaving, breaking the ability of the Senusi to recruit new fighters. Over the course of 5 years over one-hundred thousand people, the entire population of Cyrenaica, were interned in concentration camps. By the time the camps closed in 1934 around sixty thousand indigenous Libyan people had died in them. After the Italians had “pacified” Libya, the fascists settled tens of thousands of Italians in regions that had been stolen from the indigenous people. Libya functioned as an agricultural colony until the Second World War disrupted Mussolini’s ambitions. Libya became an independent state after the war but was deeply scarred by the genocide.

The Prerogative and Normative States

Historians began attempting to unpack the nature of Fascist regimes before they had even fallen. In the 1920s, and for the rest of his career, the Liberal-minded historian Gaetano Salvemini dedicated his research to discrediting Mussolini’s regime, for which he was exiled from Italy in 1925. After the end of World War Two, however, most scholarship on fascism focused on the Nazis, and when they did cover Italy it tended to be part of a generalized study of “generic Fascism”. Rather than studying a specific nation, authors such as Stanley Payne and Robert Paxton have attempted to discover a generic definition that applies to all fascisms across Europe. Only recently have the Italian colonies, and especially Libya, come under specific scrutiny by historians.

In the 1970s a group of Italian historians published a collection of essays under the title Omar al-Mukhtar: The Italian Reconquest of Libya, which was largely a political history basing its analysis of the war in archival research. The archival records translated into English in the collection have been an extremely useful source for this paper. In 2020 the historian Abdullatif Ali Ahmida traveled to Libya and did archival and oral history research in the nation and published their findings in the book Genocide in Libya, which has also been used extensively in this paper. However, neither of these works have made much attempt to connect their findings in Libya back to the Fascist regime in Rome, which is a blind spot this paper aims to fill using concepts derived from the study of generic Fascism.

In the 1940s, writing in the context of Nazi Germany, the scholar Ernst Fraenkel proposed that the nature of generic fascism was a conflict between party and state. Over the course of its reign the Nazi party had created various organizations meant to replicate government functions, but which would be loyal to Hitler alone. For example, the SS were the Nazi party’s secret police that worked in parallel with the traditional German civil and military police. Fascist Italy, too, had party-affiliated secret police (the OVRA) that functioned in tandem with the regular state police. Under Fraenkel’s interpretation these parallel organizations were deemed the “prerogative state” because they acted above or around the law. The only justifications the prerogative state needed to act were the orders of the leader along with a sense of “destiny” for their chosen people. What Fraenkel called the “normative state” was the opposite – the civil and legal institutions that were directly tied to the government. The justification for the normative state’s existence relied on the legality of its actions within the existing constitution. Fascism, then, was framed not as a static belief system, but as a continually evolving “dual state” characterized by the dominance of, at different times, the normative or prerogative state.

While Fraenkel’s interpretation saw the prerogative and normative states as separate organizations – political party and government institutions – my paper will run with a looser interpretation. The prerogative and normative states here are not comprised of literally separate entities, but instead general tendencies displayed by individual leaders within the Fascist movement. The “normative state” is the general motivation that leaders had to build a government that can function normally in day-to-day life – a “normalizing” impulse. It is the tendency to create functional institutions, to pass laws, and govern by civil police and courts. The actions of the normative state are considered legitimate based on their legality. The “prerogative state” is the more radical impulse that existed within fascism, a desire for rapid and extreme change. The prerogative state is the tendency to use violent force, might-makes-right policy, death, and punishment, to solve a problem at any cost. The prerogative state does not derive its legitimacy from law or government policy; instead, it wields violence and dares anybody to resist.

Over the course of this essay, various characters will inhabit or “use” the normative or prerogative impulse depending on what most suits their situation. As an example, general Badoglio, governor of Libya, will first attempt to “pacify” the region using normative solutions such as negotiating treaties and offering legal pardons to any rebels who surrender. When that fails, Badoglio will instead use institutionalized violence to build concentration camps in Libya. He will find the “solution” to the Libyan conflict in prerogative violence rather than normative law. No person within the Fascist regime existed solely within the prerogative or normative impulse, but instead used these separate ways of governing to accommodate whatever situation they were in. During the war in Libya these two tendencies were a source of conflict within the Fascist government which in the end collaborated to conduct a genocide that killed around sixty-thousand indigenous Libyans. It was after the war in Libya, during which the Fascist government implemented racist policies in the colony, that Mussolini saw reason to bring racism into the normative government structure, writing it into the 1938 Race Laws.

Normative and Prerogative War in Libya

By 1928, it was clear that the militaristic strategies employed by generals and governors were failing. A shakeup in leadership came in 1929, with Mussolini taking personal control of colonial affairs – although he mostly left day-to-day administration to his sub-secretary De-Bono, who had previously been the governor of Libya. De-Bono was promoted out of governorship and replaced by the new Governor Badoglio and his loyal friend vice-governor Siciliani. Badoglio saw the failure of the previous campaigns and instead attempted to create a normative state which would goad the rebels into giving up, stating:

"It is obvious that we shall never achieve our goal if this population does not feel the moral and material benefit of […] submitting to our customs, to our laws. […] To sum up, I intend […] to have officials who carry out, with full awareness and with a complete sense of their own responsibility, all, I repeat all, the functions of law and regulations that have been assigned to them."

Badoglio hoped that by showing the population of Libya the “superiority” of Italian customs and laws, they would see no need for continued rebellion. To further encourage this, he stated that any Sanusi rebel who surrendered would be given a full pardon by the government . This was, in essence, an attempt to justify the occupation of Libya based on law and precedent – Badoglio hoped to skip the military campaign and immediately create a normative state. To do this, Badoglio attempted to sign a truce with the Sanusi rebels. However, after 5 months of negotiations with Senusi leader ‘Umar al-Mukhtar, the truce broke down and hostilities resumed.

Colonial secretary De-Bono was outraged at this failure, but unable to assail Badoglio directly, instead settled for continuous attacks on Vice-Governor Siciliani’s reputation. In January of 1930 a group of Senusi troops who were believed to be loyal attacked an Italian stronghold and escaped into the desert. De-Bono, who had long held that the normative policy in Libya could only lead to failure, telegraphed Badoglio:

"We have had the encore as I predicted. […] Siciliani, I repeat, does not seem to be up to his job. Your excellency must see what measures we need to take so as to not waste our efforts. My opinion is that we shall have to resort to concentration camps, and that we should do this as soon as Tripolitania is sorted out."

Badoglio, under intense political pressure, had in fact already begun constructing concentration camps in Cyrenaica. From Rome, De-Bono engaged in political maneuvering within the normative state to bring about a more prerogative, violent attitude in Libya. De-Bono’s maneuvering outpaced Badoglio, and in January of 1930 vice-governor Siciliani was replaced with a young rising star from the Libyan campaigns, General Graziani. Graziani promised a much more active and militaristic campaign in Libya. Where the normative approach to war had failed, the prerogative approach would succeed – whatever the cost.

When Graziani entered his position, he was given orders by Mussolini which included:

"(3) Remove the [Libyan population] entirely from all Senusi influence […] (6) Use of irregular elements to fight enemy brigandry and to initiate vigorous reprisal actions, the final objective of these being to clear the territory completely of every enemy formation."

The instructions called for much crueler measures than Badoglio had previously put in place. These instructions were not justified on any grounds of legality. Mussolini wanted a violent end to the war as fast as possible – a prerogative solution. General Graziani, for his part, was all too willing to remove the population from “all Senusi influence”. He viewed the attempt at a normative peace as a failure. He also felt that so long as the Senusi Order existed it would always be a danger to Italy. He took issue both with the previous military strategies, which only attacked armed Senusi organizations but did nothing to the Libyan populace, and Badoglio’s normative attitude:

"This is how things are, and unless there is a radical cure of the entire organism [Libya], they [the Senusi] will continue like this for dozens of years to come, because I rule out military action, intensive though it may be, as a means of destroying the [Senusi], which are always ready to regroup […], turning up leaders in the encampments of the [Libyan people].

I see the situation in Cyrenaica as comparable to a poisoned organism which produces, in one part of the body, a festering bubo. […] To heal this sick body it is necessary to destroy the origin of the malady rather than its effects."

Here Graziani identifies the Libyan people, rather than the military Senusi actions, as the source of Italian problems in Libya. As Graziani saw it, a purely military “solution” to the “problem” of the Libyan people wouldn’t work. Badoglio’s approach – which established a treaty with the armed Senusi organization rather than dealing with the Libyan people – also suffered the same issue of not dealing with the source of the problem.

However, under pressure from Rome, Graziani was forced to conduct a military campaign against the Senusi. The campaign was, unsurprisingly, indecisive, resulting in few casualties on either end while the Senusi retreated to regroup in the desert. This gave Badoglio an opportunity to take the initiative again, issuing an order to Graziani in June of 1930 to conduct more repressive measures. Badoglio’s intention for the people of Libya speaks for itself:

"What path should we follow? […] We must, above all, create a large and well defined territorial gap between the rebels and the subject population. I do not conceal from myself the significance and gravity of this action, which may well spell the ruin of the so-called subject population. But from now on the path has been traced out for us and we have to follow it to the end, even if the entire population of Cyrenaica has to perish."

The purpose of creating the “well defined territorial gap” between the Senusi and the Libyan people was so that anybody found outside of a concentration camp could be considered a rebel and killed. Badoglio had now pivoted: instead of using legalistic solutions such as allowing pardons for rebels, the more prerogative approach of violent internment in camps was to be used.

Beginning in 1929, and at its highest intensity from 1930-1931, over one-hundred thousand tribespeople were forced into concentration camps on the northeast coast of Libya. The leader of the Senusi resistance, ‘Umar al-Mukhtar, was captured in September 1931 and hanged at the age of 73. In the five largest concentration camps nobody was allowed to leave without being given a special pass first. “Forced labor was common, and no serious medical aid was provided. Outside the camps, Graziani ordered the confiscation of all livestock.” The confiscation of livestock was especially devastating, including for the livestock themselves: “Rochat estimates that 90 to 95% of the sheep, goats, and horses, and possibly 80% of the cattle and camels, died by 1934”. Livestock were used by the tribespeople of Libya both for food and economic security. By 1934, around two-thirds of the people who had been forced into the camps – around sixty-thousand people – had died. Death occurred from executions, sickness, and starvation.

The prerogative strategy worked. All armed resistance to the colonial occupation had been crushed by 1932. In January of that year, Badoglio broadcasted a message to the public:

"I can state that the rebellion in Cyrenaica has been completely and definitively crushed. […] For the first time, after twenty years from landing in these countries, the two colonies are completely occupied and pacified. This fact should not only be a source of legitimate satisfaction for us all but also the point of departure for a stronger impetus towards civil progress in the two colonies."

Badoglio hoped to now extend “civil progress” – normative law and government – into Libya. “Civil progress” here was explicitly Italian normative government, as shown by Badoglio and Graziani’s continual insistence that the concentration camps remain open even after the active conflict ended. In July 1932, Badoglio sent out instructions to the Italian government in Libya:

"We need to adopt the following lines of conduct: (1) To regard any representative of the Senusi leadership as a very dangerous enemy who must always be fought […] (2) Do not try to get the refugees to return. It is better to lose them forever […] (4) The Gebel must be controlled mainly by Italian colonists […] (6) Give active attention to the running of the concentration camps so that […] the local people are convinced, or better still grow accustomed to thinking, that they are their permanent destination."

Badoglio still did not trust that the Senusi order had entirely been destroyed. So long as the Libyan population remained in concentration camps, Badoglio knew he could keep them surveilled and weak. Despite Badoglio’s directions, higher authorities had already begun dismantling the larger concentration camps. There were two likely reasons for this: that the Italian government did not have the resources to ensure food security and hygiene in the camps, and the need for “cheap manpower” to develop the colony.

In late 1932 the decision was made to break up the remaining camps and to disperse the population to their homes – with one exception. In February of 1934 Graziani announced to Italian colonists that:

"The indigenous populations have all been taken back to the regions adapted to their form of life, firmly based on the principle that the Gebel, backbone of the colony’s farming economy, must remain free of them and earmarked for mainland [Italian] colonization."

The old idea to make Libya into an agricultural colony now returned as the normative state expanded. Rather than using violence, Graziani now used economic pressure – normative governance – to discriminate against Africans. It is likely that Libyan forced labor was used to construct roads and buildings in the areas newly open to Italian settlement. Even without that, Graziani personally stated that the daily pay for Italian construction workers was 30 lire, while Arab workers were only paid 10. This was part of a larger policy intended to develop Italian economic activity in the region:

"It was necessary for the government to intervene in order to get the people to make economies for their own benefit […]. To this end, a daily sum of two lire was held back from every worker’s pay, which was paid into the postal savings book of each registered worker. The saving thus […] will go to the acquisition of animals, which will naturally remain the property of the individual savers."

Normative economic policy was being used to create an economically prosperous Italian colony.

Graziani also hoped to “Italianize” the next Libyan generation, constructing “boys camps” where Libyan children were sent to be educated. Graziani explained his motivations in 1934:

"From these training grounds of Italian culture and civil, professional and military education, will emerge the first groups of the new Libyan generation. From them the colony will be able to obtain the individuals best suited to the needs of agriculture, civil administration, [and military action]."

With the end of the war in Libya came the construction of the normative state, using economic, cultural, and eventually legal institutions to create a new Italian economic base. The laws passed in Libya would eventually extend to all Italian colonies with the 1938 Race Laws: anti miscegenation, barring Libyans from public education (other than Graziani’s boys schools), etc. These institutions explicitly favored Italian immigrants, and even attempted to create out of the next Libyan generation an Italian cultural disposition. The fascist governance of Libya had transitioned from a normative structure under Badoglio, and then into a prerogative state of war, and then back into a normative structure after the Senusi Order was destroyed. The task in Rome was now to justify the discriminatory policies pushed by Graziani and Badoglio on legal, normalistic grounds.

The Normative 1938 Race Laws

Early in the 1930s, Mussolini apparently did not see any political advantage in open racism. In fact, in 1931 he conducted a public interview where he said:

"Of course there are no pure races left; not even the Jews have kept their blood unmingled […] Race! It is a feeling, not a reality; ninety five percent, at least, is a feeling. Nothing will ever make me believe that biologically pure races can be shown to exist today. […] National pride has no need of the delirium of race."

Whether or not Mussolini personally believed what he was saying here is impossible to tell – and additionally, not relevant. What is relevant is that, in 1931, Mussolini saw political advantage in being publicly, vehemently, anti-racist. This, of course, stands in stark contrast with the “civilizing” mission that Graziani and Badoglio were conducting at the same time. Libya, however, was still a separated region from the mainland at this point – not only geographically, but also in government. Libya was run by De-Bono, Badoglio, and Graziani as a force of the prerogative state, separated from the normative laws in mainland Italy.

However, as the normative state expanded into Libya, the lines between racist legislation in the colonies and mainland Italy became blurred. By 1936 a legal system of strict separation of Italians and Africans had been created in Ethiopia. Indigenous Africans were barred from Italian public life – not allowed to attend public schools, own property, etc. In 1937 anti-miscegenation laws were promulgated across the colonies by the government in Rome.

By the late 1930s, Mussolini was actively involved in the creation of a racial ideology with other prominent racists in the Fascist movement. As the historian Aaron Gillette put it: “Mussolini felt that such a [cultural] revolution was necessary if Fascism was ever to discipline and ‘harden’ the Italian people. Racism became part of this program. A homogenous, conformist national culture would coalesce around the myth of racial homogeneity.” The creation of this racial in-group had been difficult for Mussolini. There were multiple different “schools” of racism among Fascist intellectuals, ranging from “Nordic” conceptions of race more akin to Naziism and a more “mediterranean” conception. In the end, Mussolini would declare that while a European “white” race exists, there also existed distinctive sub-groups of Italians, Germanics, etc. While the in-group proved to be difficult to construct, the enemies were easy to point out: Africans and Jews.

The inclusion of Jews in Mussolini’s new racial consciousness seems to mainly have grown out of a subset of already-existing racism within Italy, largely unconnected to the colonies . However, the motivations for racism and antisemitism were related in at least one sense. Libya had been seen, from the beginning of the invasion, as a gateway to Italian influence across the rest of the Middle East. One potential rival to Italian influence in the region was Zionism since both the Ottoman and British governments had negotiated Jewish immigration into the Levant. Many Italian Fascists saw both the Turkish and the British as Italy’s natural rivals in the Middle East – and so too, therefore, were Jews who collaborated with those rivals. Most of the legislation that targeted Jews targeted Africans in similar ways as a general effort to remove racial out-groups from public life.

In 1938 Mussolini sponsored the publication of the first edition of the magazine La Difesa della Razza (In Defense of Race). While the magazine was nominally independent from the Italian government, it was deeply connected to Mussolini and the newly created government “Office of Racial Demography” in personnel and funding. The first article published by the magazine was the Manifesto of Racial Scientists, which Mussolini had personally authored together with a team of prominent racists in the Fascist movement (although it was published anonymously). In contrast to Mussolini’s earlier proclamations that racism was “ninety five percent, at least, […] a feeling,”, the Manifesto of Racial Scientists proclaimed:

"1 Human Races exist. The existence of human races is not indeed an abstraction of our spirit, but corresponds to a real phenomenon, material, perceptible with our senses. […]

8 It is necessary to make a clear distinction between the Mediterranean peoples of Europe (western) on one side, and the Orientals and Africans on the other side. Theories that claim that some European peoples are of African origin […] are therefore dangerous, establishing absolutely inadmissible relations and ideological sympathies. […]

10 The purely European physical and psychological characteristics of the Italians must not be altered in any way. […] The purely European character of the Italians would be altered by racial mixing with any extra-European race[.]"

In the Manifesto we see the anxieties that Mussolini had about the extension of the normative state into the colonies. Without any theoretical justification for the racist policies that already existed in Ethiopia and Libya, the state in Rome risked the breakdown of its perceived homogenous national culture around a racial identity. Mussolini attempted to show that Italians are different from Africans on a biological level, and that racial mixing with “any extra-European race” threatens the Fascist state. The Manifesto laid out the basic principles that would guide the 1938 Race Laws. The violent racial character of the prerogative state, manifested in warfare and concentration camps, now took on a new legalistic methodology. The normative state had created its own violent hierarchy out of the ruins of Libya.

The Legacy of Genocide

In Libya today, the memory of the genocide continues through folk poetry. One poem, Mabi-Marad, describes daily life in one of the camps built on Badoglio’s orders:

I have no illness except about the saying of “Beat them,” / No pardon, / And “With the sword extract their labor,”

The company of people unfamiliar to us, / A low life indeed / Except for God’s help, my hands are stripped of their cunning.

I have no illness except the suppression of hardship and disease, / Worry over horses… / and work for meager wages as the whips cry out lashing.

What a wretched life, / And when they’re done with the men, they turn on the women.

According to the Ottoman census of 1910, the pre-war population of Libya was one and a half million. By 1951, the population had dropped to one million. Libya was one of the poorest nations in the world when it became independent. The Italian Fascist program had specifically targeted the educated elite; in 1950, there were only 16 university graduates in the entire population.

In 2008 the historian Ali Abdullatif Ahmida traveled to Benghazi to study the ruins of the concentration camps, which still stand today, and to interview survivors of the genocide. One of these survivors was Haj Muhammad ‘Usman al-Shami, who had been a deputy in the Senusi Order. Haj Muhammed was interred at the concentration camp known as Agaila together with his mother. When asked what had caused so much death in the concentration camp, Haj Muhammed said “we died because of Shar, evil, my son.” By Shar Haj Muhammed had meant starvation and disease, but he named them under the Arabic word for evil.

Evil would not end with the closing of the colonial concentration camps. In 1937 and 1938 a group of men from Nazi German high command made visits to the “model colony” of Libya to witness the settlement of 20,000 Italians in new villages that had been constructed in land stolen from indigenous Libyans. The commanders were invited to board the ships bringing Italians to Libya to witness the spectacle. Those who attended included Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Goring, both of whom would go on to be instrumental in the Holocaust. It is not a stretch to say that the Nazi ambition to “resettle” Eastern Europe with Germanic immigrants had been, at least in some part, inspired by the Italian colonies. The 1938 Race Laws that were passed following the Manifesto of Racial Scientists created a registry of all Jews living within Italy. This registry was used by the Nazis to find Jews during the Holocaust after their occupation of Northern Italy in 1943. The colonial project in Libya had created a desire among Mussolini and his regime for a legalistic, normative form of discrimination. The Nazi occupation brought back the prerogative “solution” to these problems, only now in Italy rather than in Africa.

The prerogative normative states in Italy had collaborated to conduct a complete destruction of the Libyan people. Whether it was the active warfare and genocidal policies of Badoglio and Graziani, or the legalistic discrimination and Italian settlement pushed by Mussolini, the intent was the same. Fascist Italy aimed to establish dominance over Libya, in the words of Badoglio, “even if the entire population of Cyrenaica has to perish.”

Bibliography

Unfortunately properly copying over all of my footnotes would be a painstaking process to do, but if anybody would like to know where I found a specific piece of information you can contact me on Discord or email me at fascopedia@protonmail.com. The full bibliography, however, can still be found below.

Ahmida, Ali Abdullatif. Genocide in Libya: Shar, a Hidden Colonial History. Milton, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Group, 2020.

Bernardini, Gene. “The Origins and Development of Racial Anti-Semitism in Fascist Italy.” The Journal of Modern History 49, no. 3 (1977): 431–53.

Livingston, Michael A. The Fascists and the Jews of Italy: Mussolini’s Race Laws, 1938–1943. Studies in Legal History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Paxton, Robert. The Anatomy of Fascism. 1st ed. New York: Vintage Books, 2005.

Santarelli, Enzo, Giorgio Rochat, Romain Rainero, and Luigi Goglia. Omar Al-Mukhtar: The Italian Reconquest of Libya. Translated by John Gilbert. London: Darf Publishers, 1986.

Vivarelli, Roberto. “Interpretations of the Origins of Fascism.” The Journal of Modern History 63, no. 1 (1991): 29–43.

You can click on any of the images to be taken to their source. All images found on Wikimedia Commons.